At first glance, this situation appears to be a long way from a discussion of evolution; however, the movement of a virus from one individual to another is similar to the founding of a new island population by a small number of migrants. Gene flow between the ancestral population and the new population is nonexistent, and the populations are free to diverge, as a result of genetic drift, adaptation to different environments, or both.

If the dentist passed his HIV infection to his patients, then the viral strains isolated from these patients should be more closely related to each other and to the dentist's strain than to strains from any other individuals living in the same area. Following this line of reasoning, Chin-Yih Ou and colleagues sequenced portions of the gene for the HIV envelope protein from viruses collected from the dentist, 10 of his patients, and several other HIV-infected individuals from the area who served as local controls.

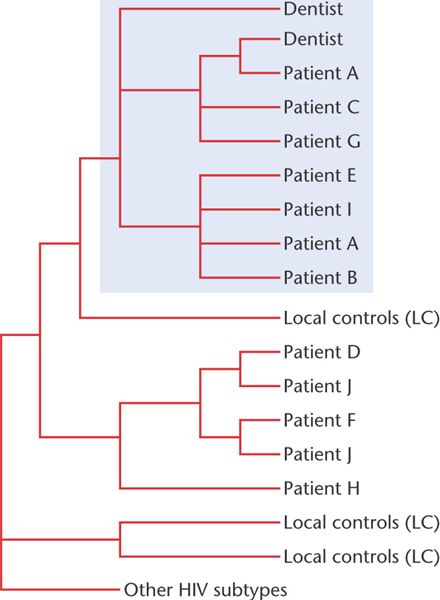

An evolutionary tree for the HIV strains produced from these sequence data is shown in Figure 26-21. The viruses isolated from the participants in the study are at the tips of the branches; branch points join these to the inferred common ancestors. The HIV samples from patients A, B, C, E, G, and I all share a more recent common ancestor with each other and with the dentist's strains than with any of the HIV samples from any of the other local individuals. The evolutionary relationship among these HIV strains indicates that the dentist did, indeed, transmit his infection to those patients. In contrast, the viruses taken from patients D, F, H, and J are all more closely related to strains from local controls (LC) than they are to the dentist's strains. These patients got their infection from someone other than the dentist. Patient J, in fact, seems to have acquired his infection from two different sources. The Centers for Disease Control, which tracks HIV cases, has not been able to determine how the dentist-to-patient transmission took place. There have been no other documented cases of provider-to-patient transmission in a healthcare setting.

[Page 657] Figure 26-21. A phylogeny of HIV strains taken from a dentist, his patients, and several local controls (LC). The group of viral strains in the shaded portion of the phylogeny are all derived from a common ancestral strain.