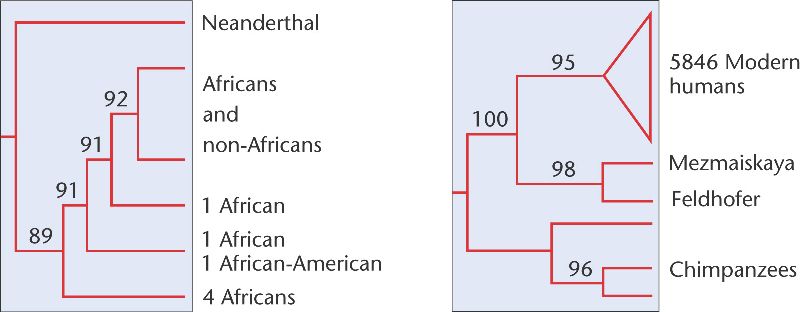

To resolve these issues, several groups have focused their attention on the recovery and analysis of DNA extracted from Neanderthal bones. In 1997, Svante Pääbo, Matthias Krings, and their colleagues extracted fragments of mitochondrial DNA from a Neanderthal skeleton found in Feldhofer cave near Düsseldorf, Germany. After confirming that they had indeed isolated Neanderthal gene fragments, the researchers placed the Neanderthal sequences on a phylogenetic tree together with sequences from more than 2000 modern humans [Figure 26-22(a)]. On the basis of Pääbo and Krings's analysis, Neanderthals appear to be a distant relative of modern humans. Using a molecular clock calibrated with chimpanzees and humans, the researchers calculated that the last common ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans lived roughly 600,000 years ago, four times as long ago as the last common ancestor of all modern humans. However, considerable caution is required when drawing conclusions based on a single Neanderthal specimen.

Figure 26-22. (a) A phylogeny estimated from mitochondrial DNA sequences of one Neanderthal and over 2000 modern humans.